A SUBJECTIVE LENS

Jim Shoemaker Photography

Start Off the New Year Right

January 2, 2018

Years ago when I lived in Michigan and trained in the martial arts, the students in our dojo had a tradition. Every New Year’s Day we would meet at the dojo and have a special class, training between two to four hours. Afterwards, we’d have a small celebration with some good food and drinks. The point of the class was twofold: 1) to reinforce discipline by making ourselves get up and go to class when we had been up late the night before, and 2) to reaffirm our dedication to studying and mastering something we all held dear.

It’s been a long time since I’ve gone out early on New Year’s Day to swing a Bo staff around, and I'm reasonably sure that if I did that here in southern California someone would call the police on me. These days, I like to go out with my camera and spend some time shooting. On some occasions I have been able to drag my weary body up into the mountains to catch the first sunrise of the new year. Other times I just go out and look for anything that I find interesting. The goal of the exercise is not photographing any particular thing, nor photographing for a particular amount of time. It’s simply to make myself go out and photograph when I’d much rather sit on the couch and watch some football.

morePhotographic Snobbery

December 26, 2017

For a discipline such a photography, which is wide in scope of subject matter and diverse in artistic styles, I find it odd that there is a lot of elitism and snobbery. I’ve written in previous posts about the tribal tendencies of humans, and the field of photography is not only no exception, it may be an extreme example.

There is never ending battle of gear and technologies—Canon vs. Nikon, large format vs. medium format vs. 35mm format, prime lenses vs. zoom lenses, digital vs. analog, RAW vs. JPG, CF vs SD, etc. ad nauseam. There is also the narrow mindset of, “The way I approach photography is the correct way and if you’re doing it differently then you’re doing it wrong.” And of course, the elitist viewpoint that a degree from a collegiate photography program trumps self-teaching.

Just as within the movie, music and television industries, new technology in photography has rendered the gate-keepers obsolete. There used to be a time when if you wanted to produce a TV show, you had to be green-lighted by a studio. Those days are long gone. Now companies like Netflix and even Amazon are producing award-winning programs. Home studios and amazing software have allowed musicians to produce their own professional-quality recordings without selling all of their rights to a record label. Likewise, advanced cameras and editing software have made their way into the hands of photography enthusiasts around the world, enabling even the most fledgling photographer to create images that professionals from decades past would have been hard pressed to match.

morePreparing for Disaster

December 5, 2017

I woke up this morning to discover there were multiple wildfires burning in southern California. While the nearest fire is over 20 miles from where we live, the fires virtually surround us to the east, north and west. The air is filled with smoke and it feels very apocalyptic. Although this is sadly a fairly common occurrence when the Santa Ana winds arrive after no rain has fallen in October or November, it’s a good opportunity to review a few things that serious photographers should keep in mind when dealing with natural or man-made disasters. I’m only going to address photography-related issues, since if you live in earthquake, fire, hurricane or tornado country you should already have evacuation plans, food, water, batteries and other emergency supplies in place.

The first thing that I highly recommend doing is insuring your gear. If you’re a professional working photographer, you probably have a fair amount of gear ranging from multiple camera bodies in multiple formats, lenses, tripods, strobes and speedlites, light modifiers, light stands, storage cases, etc. If you’ve been shooting and acquiring gear over many years, you may not even realize how much you’ve stockpiled. Don’t forget filters and grip gear, which can add up to several hundred if not thousands of dollars by themselves.

moreThe Myth of Bad Light

November 28, 2017

A few years ago I was photographing at the south rim of the Grand Canyon at sunrise. A German tourist approached me and started a conversation, and after a while as the sun climbed higher in the sky, I stopped shooting. Noticing this, he asked why I stopped and I told him the light had become too harsh for the type of images I was trying to make. He said, “Ah, so the light has become evil then?” The comment made me laugh, but it also made me stop and think about how photographers view light.

You won’t have to look very hard to find books, magazine or online articles with titles like, Shooting in Crappy Light, Taming the Mid-Day Sun and How to Make Great Photographs In Bad Light. But what is “bad” light, and does such a thing even exist?

In my commercial work of environmental portraiture, it’s common to have the client want to be photographed outside in front of a corporate building or on an industrial campus. It’s also sadly common that the only available time they have in their schedule to shoot is 11:30am or 1pm, or some other time of day where the sun is directly overhead and creating harsh lighting. If I place my subject under that light the results aren’t going to be pretty. My inclination in that type of situation is to look for open shade of any kind; a place that offers even lighting that I can control relatively easily. If I can’t find any open shade or the client has a specific location they want to use that doesn’t offer any, then I have to build scrims, use reflectors or introduce flash into the equation. This is the hassle and heartbreak that created the myth of “bad” light; situations where photographers have to struggle and wrestle with the light in an attempt to conquer it rather than having the flexibility to work with it. To take advantage of the available conditions, I like to use the sun as a rim light or accent light, saving me the trouble of setting up another flash and also giving me a sense of having turned the light to my advantage.

moreThere's No Place Like Home

November 21, 2017

After spending several months on the road over the course of the past year it feels good to be home, especially as the holidays approach. It also allows me to focus my attention to more familiar subjects for photography. A common misconception is that in order to find interesting subjects, you have to travel to distant, exotic locations. While it’s true that you’ll undoubtedly find photogenic subjects in such places, a good photographer needs to be able to make interesting images anywhere.

In my commercial work of environmental portraiture, there have been many times when I arrive at an office or business and am told that the only available space to photograph my subjects is an area used for storage, or a hallway, or some other uninspiring and cramped location. In those instances I use my lights and modifiers to try to make the scene visually interesting, and finding and making use of interesting light is the key to making local landscape images dramatic as well.

I’m fortunate to have the Santa Monica Mountains in my back yard; a Transverse Range that extends from Hollywood to Pt. Mugu, north of Malibu. Compared to the Grand Teton, Rocky, Sierra Nevada, Cascade or San Juan Mountains, the Santa Monica range is humble and subdued, with the highest point being Sandstone Peak. Clocking in at 3,111 feet, it just clears the required 3,000 feet required to be categorized as a mountain. The Backbone Trail runs 67 miles along the spine of the range. My wife and I have hiked the entire trail, and certain sections of it have become favorite places for me to return time and again with my camera in tow.

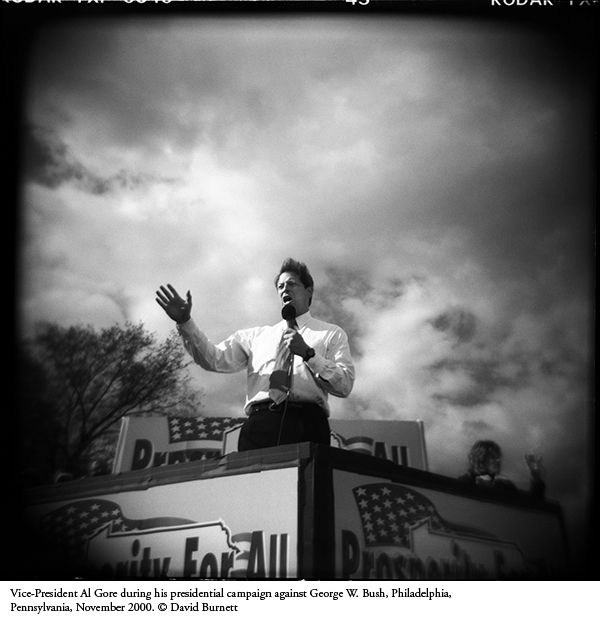

moreMaking the Journey the Destination

I recently returned from an extended photographic trip throughout sections of Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. On trips such as this one, I generally leave home with a rough outline of an itinerary deliberately left nebulous and vague. I have a broad idea of where I want to go and what I want to photograph, then point my truck in the appropriate direction and hit the road.

It’s said that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, but I never drive one. I wander. Or maybe meander. Whatever it is I do, it could be said that I sometimes take the most circuitous route possible from Point A to Point B. In the age of electronic navigation, it’s not because I can’t find my way. It’s because of all the interesting things I find that I never knew existed. The things I discover in and around towns few people have ever heard of; the breath-taking scenery and hidden gems I uncover in “Fly Over” states (a term that takes me laugh every time I hear it) that enhance my life and make me richer for the experience.

I often revisit areas I’ve been to many times, but each time I like to explore new roads (sometimes a very loose term) and trails I’ve never been on before. If I turned left last year I’ll turn right this year. It may seem like a waste of time but it never is—even if I don’t produce any photos as a result—because I’ve encountered something new about a place that I thought I was familiar with, and the more intimate I become with a place the better I can represent it in a photograph.

moreConfusing the Subject for the Photograph

There is a phenomena I’ve noticed, especially online, regarding how people respond to photographs. In particular, what it is that will trigger someone to respond positively and regard a photograph as “good”. There are a number of things that a trained photographer, either formally or self-taught, will look for in a photograph during a critique. Technical aspects such as focus and effective use of depth-of-field, and artistic choices such as framing, spatial relationships between fore, middle and background, and choice of lighting. Elements of art such as line, shape, form, color, etc, and successfulness of expressing a concept, idea or emotion. But many times I have seen photos that are technically imperfect, devoid of artistic flavor and seem to say nothing. Yet they are highly complimented and rated. Why is that?

My answer is what I call “confusing the subject with the photograph”. Let me give you an example. A person shows a group of friends a photograph of their newborn baby. Everybody admires it and comments on what a great photo it is. But is it a great photo, or a great subject? For another example, let’s consider the deluge of selfies of scantily-dressed women that are posted to social media on any given day. There’s no shortage of men who will comment on how great the photos are, but considering that these images are generally made by a woman standing in her bathroom, lit by fluorescent lights and pointing a smartphone camera into a mirror, I don’t think I need to spend a lot of time arguing that the lighting and styling of the photograph aren’t exactly artistic or even ideal.

moreBreaking the Inertia

Last week I returned from a month-long road trip. I’ve been on the road a lot lately. In fact, I’ve put over 18,000 miles on my truck since July 1st of this year. I’ve been doing a lot of driving, a lot of hiking (well over 100 miles) and a lot of photography. What I haven’t been doing is a lot of writing. I carry my laptop with me, ostensibly to write blog posts in my spare time, but after a day of lugging all my camera gear through 14 miles of Utah canyons, when I get back to my truck I feel less like writing and more like passing out. String together days, then weeks, of that kind of activity and you end up with a lot of blank pages in your blog.

The situation lead me to think about the times I’ve felt the same way about taking the camera out to make some photographs. There have been days during my photography trips when it’s raining, or very windy, or snowing, or blazing hot or freezing cold. This past summer and fall I was caught in many hail storms in Colorado and South Dakota, and was temporarily trapped by a flash flood in a mountain basin in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado. There are many days when my muscles are sore and feet ripped up from the previous day’s marathon hike. Days when I’m tired because I’ve strung together several consecutive nights with four hours or less of sleep. Days when the light is too harsh or too bland for the photos I wanted to make. Days when I feel completely burned out or unenthused.

moreBe Fluid

One thing I have learned as a landscape photographer is the ability to adapt to rapidly changing situations. I can tell you from nearly 14 years of experience on the road that things rarely go according to plan. In the early days I would struggle against unforeseen circumstances and try to force my predetermined agenda to work in an environment it was no longer suited for. These days I try to roll with the changes, not only because I tend to get better results, but also because it’s the path of least resistance.

The plan is now just a guideline. It’s a framework but within that framework there should be a lot of room to maneuver. At the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, a tenor saxophonist named Paul Gonsalves was playing on stage with Duke Ellington’s orchestra. They were performing Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue when Ellington gave Gonzales a solo. Gonzales improvised for 27 choruses, bringing the audience to its feet. The written score was the plan, but it became a little more than a safety net. Like Gonzales, a good photographer should have an open and nimble mind, capable of seizing an opportunity and running with it.

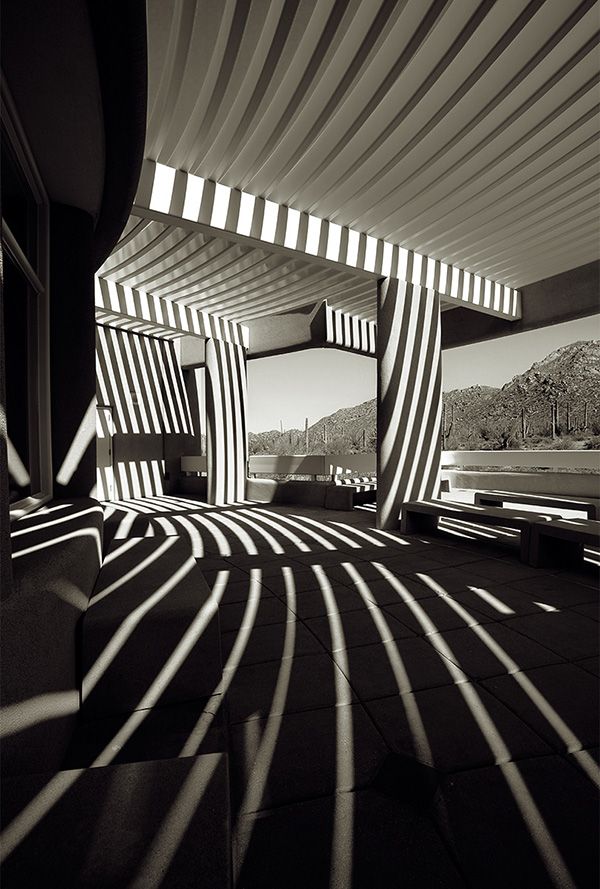

A common example from a typical road trip would be that I am hoping for a beautiful sunrise with dramatic clouds in the sky. The reality is that I rarely get them. So if the sky is clear does that mean it’s time to throw the gear back into the truck and call it a day? No, it’s just time to switch gears. Empty skies usually mean wide landscape shots are not optimal, but tighter, intimate landscape shots may work. Also, the contrasting light is favorable to black & white photographs. Maybe instead of documentary style photography, finding shapes, patterns and textures to create abstract designs would work.

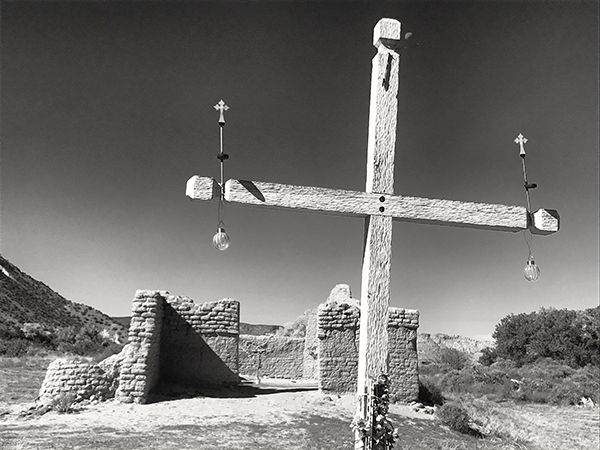

moreRiding the Rails in the San Juan Mountains

I have a deep-rooted interest in history, and it’s reflected in the subject matter that I enjoy photographing. Ghost towns, mining towns from the 1800’s, Native American ruins, Spanish Missions from the colonial days, Native American rock art and American Civil War reenactments are some of the things that attract me and capture my imagination. So it’s no surprise that when I had an opportunity to ride on an old-fashioned steam train over the Fourth of July holiday weekend, I jumped at the chance.

My wife and I met with other family members in Chama, New Mexico, home of the Cumbres & Toltec Narrow Gauge Railroad. The section of rail we would be traveling on was originally constructed in 1880 as part of the Rio Grande Railroad’s San Juan Extension, which was designed to serve the mining district of the San Juan Mountains in southwestern Colorado. Rather than boarding the train in Chama and riding to it’s terminus in Antonito, Colorado, we took a bus to Antonito and rode the train back into New Mexico. It had been suggested to us that that north to south was the best direction to travel since Antonito is in a desert environment, and it can be a bit anticlimactic after traveling through the mountains and forests nearer to Chama.

morePhotographing Fireworks Displays

Independence Day is just around the corner here in the US, so I thought I’d use this week’s blog to suggest some tips for those who want to photograph fireworks displays. It’s easy to do and doesn’t require a lot of expensive gear, so why not give it a try?

I use a Canon 5D MK III or Canon 5Ds R for my shots, depending on how large a file I want, but any DSLR will work providing it allows for manual setting of exposure time. I attach a cable release to my camera and mount it on a solid tripod. (I use a Gitzo 5563 but you don’t need anything that elaborate; just a stable mount for the camera.) I then set the camera exposure to the Bulb setting. This allows me to lock the shutter open for however long I want; capturing multiple fireworks bursts in a single frame. The longer the exposure time, the more bursts you will capture and the longer the “trails” of the bursts will be. Note however, that the more bursts you record, the more exposure you’re allowing and you could accidentally overexpose your image.

Since I generally use wide angle focal lengths in the 16mm - 24mm range for fireworks, there is a lot of depth-of-field built in so a small aperture is not necessary. I usually use f/8 or f/11, depending on how frequent the bursts are. If the fireworks are being shot off at a fast pace, f/11 may work better to keep multiple bursts from overexposing the image.

moreBe the Next Ansel Adams!

There is a particular magazine that I subscribe to that caters to nature and outdoor photography. I have been reading it for well over a decade and love it, and God bless them, they’ve featured my work multiple times over the years. Still, I have a private running joke about how many times in one calendar year that a photo of Yosemite will appear on the cover. And, at least once a year, there will be an article titled something along the lines of, Be the Next Ansel Adams! or Shoot Like Ansel Adams!

I love Ansel Adams, but I’m not delusional enough to think that I’m ever going to shoot like him. No magazine article is going to hold the magic key for me. Years ago I educated myself in photography by reading Ansel’s books. I can guarantee that over the course of his lifetime, he forgot more about photography than I’ll ever learn. But these types of articles got me to thinking about something a little deeper; about hero-worship and personal style.

In the summer of 2004 I was driving through the desert in Nevada on Highway 95, heading to the old mining town of Goldfield. I was a newbie with a camera, and was out shooting one of my favorite subjects; ghost towns. I was listening to the radio to help pass the time driving through endless miles of brown, sandy landscape. There was a story about Ray Charles, who had just passed away, on NPR. During the course of the story, the radio host related a story about a conversation Ray had with a friend during the early days of Ray’s career. One day his friend approached him and exclaimed, “Ray, you’re going to be huge! You sound just like Nat King Cole!” To which Ray Charles replied, “I don’t want to sound like Nat King Cole. I want to sound like Ray Charles.”

moreTo Crop or Not To Crop?

Have you ever heard the photography adage, “If you crop, you lose?” It’s a mantra that is regularly recited by photography “purists” (a nebulous designation with somewhat random and sometimes contradictory philosophies). I won’t argue with the spirit of the adage; that there should be careful consideration of what is or is not included within any frame and that it should, ideally, be done at the time of exposure and not as an afterthought in the darkroom or in Photoshop.

But as with any tool or technique in photography, it has its legitimate place within the craft. Photography is not simply about making a pretty picture, creating “art” or satisfying a need for a particular image. It’s about problem solving. How are you going to create the image the client has specified, or that you have envisioned? What camera will you use? What lighting? What lens?

As with all problems I encounter, I generally don’t have a cookie cutter solution. Every job and problem is unique. I have a hierarchical checklist of sorts that I will run through to determine the best course of action. For cropping, the list would go something like this:

First question: Do I have a longer focal length lens with me that would give me a tighter frame on my subject so that I don’t have to crop? If the answer is yes, then I’d change lenses. But there is more to consider.

moreWhy Does This Happen To Me?

Have you ever gone on a photography trip and had such a miserable time that you wanted to throw your camera gear out the window and give up? Have you ever felt like some great cosmic force was picking on you; that the Camera Gods were angry and chose you as the target to vent their rage? That you were insanely unlucky?

I’ve had some spectacular misadventures that occurred during my road trips. In 2015 my truck was broadsided by a deer (yes, a deer hit me) in Cedar Edge, Colorado and tore off my passenger side mirror, damaged the door and ripped off my antennae. On the coast of Oregon my Leaf Aptus digital back detached from my Mamiya 645AFD and bounced down an incline of basalt before coming to rest in a tidal pool. In the Sonoran desert of Arizona I packed up my gear late one night after a long day of shooting and inadvertently forgot to load my Gitzo 5561 tripod back into my truck before driving away, and after discovering it was missing, drove 90 miles back to the location to find someone had already found and took it.

Weather rarely cooperates, whether it means empty blue skies when clouds were forecasted or a blizzard when mild temperatures were forecasted. In 2012 I went to Crater Lake, Oregon in April. The weather forecast called for blue skies and daytime temperatures in the low 60’s. It sounded great, but I arrived at Crater Lake in the middle of a blizzard and the temperatures were in the low 30’s. I was dressed in a T-shirt, shorts and sandals, which I had put on that morning after camping in Northern California. In 2013 I drove to Big Bend, Texas in April and the weather forecast said it would be 108 every day of the week. It was warm the first night I arrived, but I woke up early the next morning to howling winds and a temperature of 42 degrees. The temperature never rose above 50 that day, and it took a week for the temperatures to climb back into the 90’s. The strong winds stuck around for the entire trip.

moreWhat's Old is New Again

I wrote in an earlier post about how photography can be different things to different people. People practice photography for myriad reasons, and since humans are tribal creatures, no matter what you choose for subject matter or what equipment you work with, there will always be somebody who will gleefully tell you that you’re doing it all wrong.

Historically, possibly the largest tear in the fabric of photography has been the chasm that exists between “pros” and “amateurs”. Back in the days of film (and more so back to the days of wet collodion), there was a steeper learning curve and the field was more self-selective. The professionals were the gatekeepers who decided who was, or wasn’t, a photographer. With the advent of digital cameras, which grow increasingly intelligent and user friendly, that gap between professional and amateur has decreased. Consequently, there has been an increasing grumbling in the professional community. The market has become flooded by amateur photographers who post their work to micro-stock agencies, build websites and start their own portrait studios regardless of whether or not they have the technical skill and talent.

“Those point-and-shoot digital cameras!” the “pros” mutter. “Everybody and their cousin thinks they’re a photographer now!” But if you know anything about the history of photography, you’ll know that this attitude isn’t exclusive to digital cameras. In fact, the phenomenon dates back to the late 1800s, before Photography as an art or science was even 40 years old.

moreMake Your Own Luck

There have been many times when I’ve looked through books by Ansel Adams, Philip Hyde, David Muench, Guy Tal and others, and after viewing one amazing image after another thought to myself, “How does one person get so lucky when it comes to finding such great light or such a magnificent scene?” It seems unfair, like maybe things could be distributed a little more evenly among more photographers. Like me.

I spend months on the road every year, and more often than not I’m skunked by the weather or something else that results in less than optimal conditions. But then there are also times when I, as Ansel Adams once said, “get to places just when God’s ready to have someone click the shutter.”

When it comes to locations, I have only so much control over what I get. I can try to be in Colorado and Wyoming when the leaves are at their peak color in the autumn, in the desert after a rainy winter when the wildflowers appear, or in the mountain basins when the wildflowers bloom in the summer. Even though it happens at roughly the same time of year, it’s difficult nailing the timing down. And when it comes to weather, the forecasts are wrong far more often than not, and in the mountains weather can change drastically within minutes. So how did Adams manage to capture so many amazing moments? Why was he so “lucky”?

moreHave Your Own Vision

Over the past twelve years I’ve had a lot of interesting experiences while photographing around the American West. I’ve met a lot of nice people and have seen many beautiful places. There is one situation though that has always agitated me to some degree, and recently it has been occurring at an increasing rate. I would like to share it because I’m certain there are other photographers out there who have experienced the same thing.

Sometimes when I’m at a location, after spending time scouting the site and putting careful consideration into how I want to frame the scene based on the light and the story I want to tell, I will set up my tripod and camera and in an instant I’ll be surrounded by a small crowd of people trying to shoot over my shoulder. Where did they come from, and why are they huddled around me?

In the Ansel Adams biography Looking At Ansel Adams: The Photographs and the Man written by Andrea G. Stillman, there is a passage about how when Ansel would set up his camera, nearby photographers would clamor around him and set up their own tripods, trying to capture whatever scene the master had envisioned. I can understand the allure of sidling up to a photographer like Adams, Art Wolfe, Jack Dykinga, Jim Richardson or many other well known landscape photographers and “borrowing” a frame from them. But I’m not Adams, or Wolfe, or anybody that anyone would recognize or know about. The only explanation that I have is that they see the tripod, the “pro” camera and assume I must know what I’m doing. (That’s a mistake. I’m the guy who should have the bumper sticker on my truck that reads, “Don’t Follow Me: I’m Lost.”)

moreDon't Turn Your Camera Into A Pseudoreligion

Minor White once said that photography is a religion. A student of Zen, White’s comment referenced the amount of study, devotion and effort that a photographer dedicates to the craft. But like any religion, it can be taken to extremism, and when extremism mixes with fanaticism things can quickly begin to go awry.

Humans are tribal creatures, and we’ll infinitely subcategorize ourselves into the tiniest boxes possible. You won’t be practicing photography very long before you encounter the question that should make your skin crawl; “Nikon or Canon?” Yes, there are many camera companies out there but nobody has created legions of rabid fanatics like Nikon and Canon have.

So what’s all the fuss? As a quick primer for the uninitiated, Canon (or Nikon, depending on which flavor of cool-aid you drank) is THE world-leading innovator of cameras, lenses and speedlites. On the other hand, Nikon (or Canon) peddles the most horrible, unergonomic and unreliable garbage ever produced and no self-respecting professional photographer would be caught DEAD using it.

A typical fanatical rant may sound like this (using Nikon only as an example): “Nikon leads the industry in innovation. Every major development in cameras, especially DSLR’s, has been made by Nikon. Nikon cameras feel sleek and smooth in the hand, while Canon cameras feel like bricks. Nikon glass is infinitely superior to Canon lenses, which is why NASA uses them on space missions. All the greatest pro photographers use or used Nikons, and my personal Nikon camera is so incredible that I don’t even need to remove the lens cap to make amazing photographs. They aren’t manufactured in a factory like lousy Canon cameras; they’re created in the heavens by the Camera Gods Themselves and delivered to the faithful and righteous on the wings of cherubs.”

moreKeep Your Tool Box Full

I mentioned in a previous post about the tribalism of human beings. We like to categorize ourselves and each other by race, politics, religion and brand loyalty to automobiles, computers, smartphones, cameras, sports teams and much more.

So it isn’t surprising that there is so much debate and controversy (not to mention animosity) over every aspect of photography. Which company makes the best cameras: Canon or Nikon? Which medium is best: film or digital? Which is a better art form: Black & White or Color? Which format is best: Large, medium or 35mm? What kind of lens is best: prime or zoom? Which software is best: Photoshop or Lightroom? Which recording format is best: RAW or JPEG? What exposure method is best: Manual, Aperture Priority or Shutter Priority? Which off-camera flash setting is best: Manual or ETTL?

The questions above are common but incomplete. The question shouldn’t be “What is the best tool?”, but rather “What is the best tool for the task I need to perform?”

There are some issues that can be technically addressed, such as when debating between using a prime lens or a zoom lens. Years ago the choice was clear. Because it’s relatively easier to construct a single focal length lens and correct aberrations, they have generally been considerably sharper than zoom lenses. With advancing technology though, the differences in image quality has been greatly reduced. These days it’s more of an issue of convenience or practicality, not to mention budget.

moreWhat Is Photography?

Lately I’ve been reading about the origins and evolution of photography. After the official announcement of Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre’s process on January 7, 1839, people were enamored by the incredible, almost magical new invention. But what exactly was it for? Was it a form of art, like painting and drawing? Or was it strictly a recording, documentation and replication process?

Throughout the subsequent years photography morphed from photogravure; pictorial attempts at imitating painting (via Demachy, Emmerson and Evans) to pre-photojournalism (via Matthew Brady and Alexander Gardner) to capturing more candid moments of “real” life (via Steiglitz and Steichen) to social photojournalism (via Riis, Hine and Lange) to straightforward representational photography with great sharpness and depth of field (via Strand, Weston, Adams and Cunningham) to Bauhaus and Surrealism (via Maholy-Nagy and Man-Ray). It would be more realistic to say that rather than a linear progression of development, photography was spreading out in various directions like ripples on the surface of a pond.

Given the multiple schools of thought we’re still left with the question; What is photography? Photographers in the group f/64 would probably took a dim view of Man-Ray’s work, and vice versa. But is one “right” and the other “wrong”? Is it even possible to have an objective definition of the medium or how to apply it? It’s similar to believing there was a “correct” way to apply paint to a canvas until Jackson Pollock came along.

more