For a discipline such a photography, which is wide in scope of subject matter and diverse in artistic styles, I find it odd that there is a lot of elitism and snobbery. I’ve written in previous posts about the tribal tendencies of humans, and the field of photography is not only no exception, it may be an extreme example.

There is never ending battle of gear and technologies—Canon vs. Nikon, large format vs. medium format vs. 35mm format, prime lenses vs. zoom lenses, digital vs. analog, RAW vs. JPG, CF vs SD, etc. ad nauseam. There is also the narrow mindset of, “The way I approach photography is the correct way and if you’re doing it differently then you’re doing it wrong.” And of course, the elitist viewpoint that a degree from a collegiate photography program trumps self-teaching.

Just as within the movie, music and television industries, new technology in photography has rendered the gate-keepers obsolete. There used to be a time when if you wanted to produce a TV show, you had to be green-lighted by a studio. Those days are long gone. Now companies like Netflix and even Amazon are producing award-winning programs. Home studios and amazing software have allowed musicians to produce their own professional-quality recordings without selling all of their rights to a record label. Likewise, advanced cameras and editing software have made their way into the hands of photography enthusiasts around the world, enabling even the most fledgling photographer to create images that professionals from decades past would have been hard pressed to match.

I have read comments online from professional studio photographers lamenting the influx of amateur photographers into the market. While I absolutely agree that amateur photographers who undercharge for their work damage the industry as a whole, those who charge appropriate prices and have the skill set to back it up should not be ostracized. If, as a long-established professional, you are having trouble competing with amateurs because the quality of their work rivals yours, then perhaps it’s time to reexamine your own skills and business model rather than writing negative comments about your competition.

There is the misconception—or delusion—that if you’re not equipped with the latest and greatest Nikanon 80mp-600-focus-point-64-frames-per-second-burst-speed-ISO 200,000,000 camera that you’re just not a professional. If you aren’t toting a Leica equipped with a $12,000 zeiss lens or a $60,000 Hasselblad with a digital back, then you need to step up to the “big boy” gear. I’m not sure where this attitude comes from—aside from being either fabulously wealthy or hopelessly in debt—but I know of people who make twice as much money as I do while using equipment that costs half as much as my own.

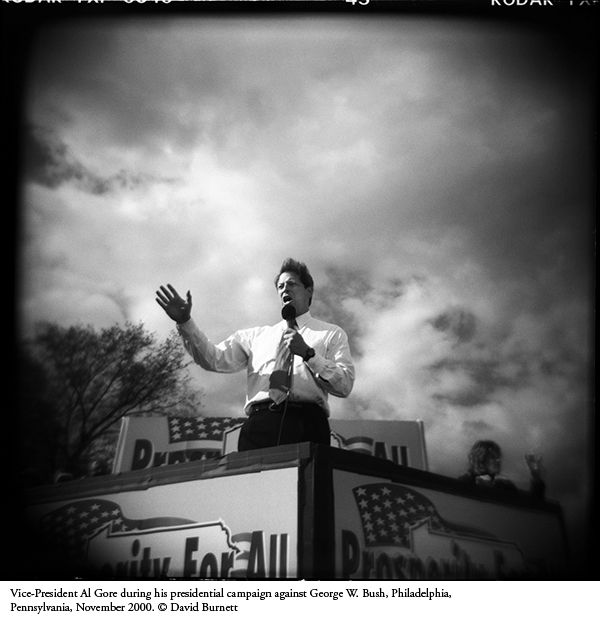

As a photographer, how many times have you heard the saying, “It’s not the camera; it’s the person behind it”? Ironically, some of the people who are fond of repeating the phrase are the same ones who will smirk when they see someone with gear that they deem to be inferior to their own. I have included at the top of this post a photograph which I find amazing, made by David Burnett. (If you’re not familiar with his name then it’s Google time.) The subject is Al Gore, made during his presidential campaign in 2000. It is a simple yet powerful black and white image that was made with… a Holga. For those unfamiliar with the Holga, it is essentially a toy camera. It’s constructed entirely of plastic, including the lens. It has a switch for two aperture settings, although the switch doesn’t actually connect with anything and there is only one, which has been argued to be f/8 or f/11. (The faux switch is supposed to toggle between the two.) It has one shutter speed and I have seen it listed anywhere between 1/80 to 1/125/second. It has no meter. It’s famous for having light leaks. It barely functions as a camera, but in the hands of a master photographer it becomes a brilliant storytelling device.

Big Boy gear? Only if you need it as a crutch.

Photography should be open to and accepting of all who want to attempt to master the craft. I heartily encourage doing just that; dedicating the time and effort to mastering it rather than allowing the gear to dictate the method of exposure and do the work for you. Anyone who is willing to put in the time and shed some blood, sweat and tears will always have a place within the arts.