A SUBJECTIVE LENS

Jim Shoemaker Photography

Start Off the New Year Right

January 2, 2018

Years ago when I lived in Michigan and trained in the martial arts, the students in our dojo had a tradition. Every New Year’s Day we would meet at the dojo and have a special class, training between two to four hours. Afterwards, we’d have a small celebration with some good food and drinks. The point of the class was twofold: 1) to reinforce discipline by making ourselves get up and go to class when we had been up late the night before, and 2) to reaffirm our dedication to studying and mastering something we all held dear.

It’s been a long time since I’ve gone out early on New Year’s Day to swing a Bo staff around, and I'm reasonably sure that if I did that here in southern California someone would call the police on me. These days, I like to go out with my camera and spend some time shooting. On some occasions I have been able to drag my weary body up into the mountains to catch the first sunrise of the new year. Other times I just go out and look for anything that I find interesting. The goal of the exercise is not photographing any particular thing, nor photographing for a particular amount of time. It’s simply to make myself go out and photograph when I’d much rather sit on the couch and watch some football.

morePhotographic Snobbery

December 26, 2017

For a discipline such a photography, which is wide in scope of subject matter and diverse in artistic styles, I find it odd that there is a lot of elitism and snobbery. I’ve written in previous posts about the tribal tendencies of humans, and the field of photography is not only no exception, it may be an extreme example.

There is never ending battle of gear and technologies—Canon vs. Nikon, large format vs. medium format vs. 35mm format, prime lenses vs. zoom lenses, digital vs. analog, RAW vs. JPG, CF vs SD, etc. ad nauseam. There is also the narrow mindset of, “The way I approach photography is the correct way and if you’re doing it differently then you’re doing it wrong.” And of course, the elitist viewpoint that a degree from a collegiate photography program trumps self-teaching.

Just as within the movie, music and television industries, new technology in photography has rendered the gate-keepers obsolete. There used to be a time when if you wanted to produce a TV show, you had to be green-lighted by a studio. Those days are long gone. Now companies like Netflix and even Amazon are producing award-winning programs. Home studios and amazing software have allowed musicians to produce their own professional-quality recordings without selling all of their rights to a record label. Likewise, advanced cameras and editing software have made their way into the hands of photography enthusiasts around the world, enabling even the most fledgling photographer to create images that professionals from decades past would have been hard pressed to match.

morePreparing for Disaster

December 5, 2017

I woke up this morning to discover there were multiple wildfires burning in southern California. While the nearest fire is over 20 miles from where we live, the fires virtually surround us to the east, north and west. The air is filled with smoke and it feels very apocalyptic. Although this is sadly a fairly common occurrence when the Santa Ana winds arrive after no rain has fallen in October or November, it’s a good opportunity to review a few things that serious photographers should keep in mind when dealing with natural or man-made disasters. I’m only going to address photography-related issues, since if you live in earthquake, fire, hurricane or tornado country you should already have evacuation plans, food, water, batteries and other emergency supplies in place.

The first thing that I highly recommend doing is insuring your gear. If you’re a professional working photographer, you probably have a fair amount of gear ranging from multiple camera bodies in multiple formats, lenses, tripods, strobes and speedlites, light modifiers, light stands, storage cases, etc. If you’ve been shooting and acquiring gear over many years, you may not even realize how much you’ve stockpiled. Don’t forget filters and grip gear, which can add up to several hundred if not thousands of dollars by themselves.

moreThe Myth of Bad Light

November 28, 2017

A few years ago I was photographing at the south rim of the Grand Canyon at sunrise. A German tourist approached me and started a conversation, and after a while as the sun climbed higher in the sky, I stopped shooting. Noticing this, he asked why I stopped and I told him the light had become too harsh for the type of images I was trying to make. He said, “Ah, so the light has become evil then?” The comment made me laugh, but it also made me stop and think about how photographers view light.

You won’t have to look very hard to find books, magazine or online articles with titles like, Shooting in Crappy Light, Taming the Mid-Day Sun and How to Make Great Photographs In Bad Light. But what is “bad” light, and does such a thing even exist?

In my commercial work of environmental portraiture, it’s common to have the client want to be photographed outside in front of a corporate building or on an industrial campus. It’s also sadly common that the only available time they have in their schedule to shoot is 11:30am or 1pm, or some other time of day where the sun is directly overhead and creating harsh lighting. If I place my subject under that light the results aren’t going to be pretty. My inclination in that type of situation is to look for open shade of any kind; a place that offers even lighting that I can control relatively easily. If I can’t find any open shade or the client has a specific location they want to use that doesn’t offer any, then I have to build scrims, use reflectors or introduce flash into the equation. This is the hassle and heartbreak that created the myth of “bad” light; situations where photographers have to struggle and wrestle with the light in an attempt to conquer it rather than having the flexibility to work with it. To take advantage of the available conditions, I like to use the sun as a rim light or accent light, saving me the trouble of setting up another flash and also giving me a sense of having turned the light to my advantage.

moreThere's No Place Like Home

November 21, 2017

After spending several months on the road over the course of the past year it feels good to be home, especially as the holidays approach. It also allows me to focus my attention to more familiar subjects for photography. A common misconception is that in order to find interesting subjects, you have to travel to distant, exotic locations. While it’s true that you’ll undoubtedly find photogenic subjects in such places, a good photographer needs to be able to make interesting images anywhere.

In my commercial work of environmental portraiture, there have been many times when I arrive at an office or business and am told that the only available space to photograph my subjects is an area used for storage, or a hallway, or some other uninspiring and cramped location. In those instances I use my lights and modifiers to try to make the scene visually interesting, and finding and making use of interesting light is the key to making local landscape images dramatic as well.

I’m fortunate to have the Santa Monica Mountains in my back yard; a Transverse Range that extends from Hollywood to Pt. Mugu, north of Malibu. Compared to the Grand Teton, Rocky, Sierra Nevada, Cascade or San Juan Mountains, the Santa Monica range is humble and subdued, with the highest point being Sandstone Peak. Clocking in at 3,111 feet, it just clears the required 3,000 feet required to be categorized as a mountain. The Backbone Trail runs 67 miles along the spine of the range. My wife and I have hiked the entire trail, and certain sections of it have become favorite places for me to return time and again with my camera in tow.

moreMaking the Journey the Destination

I recently returned from an extended photographic trip throughout sections of Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. On trips such as this one, I generally leave home with a rough outline of an itinerary deliberately left nebulous and vague. I have a broad idea of where I want to go and what I want to photograph, then point my truck in the appropriate direction and hit the road.

It’s said that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, but I never drive one. I wander. Or maybe meander. Whatever it is I do, it could be said that I sometimes take the most circuitous route possible from Point A to Point B. In the age of electronic navigation, it’s not because I can’t find my way. It’s because of all the interesting things I find that I never knew existed. The things I discover in and around towns few people have ever heard of; the breath-taking scenery and hidden gems I uncover in “Fly Over” states (a term that takes me laugh every time I hear it) that enhance my life and make me richer for the experience.

I often revisit areas I’ve been to many times, but each time I like to explore new roads (sometimes a very loose term) and trails I’ve never been on before. If I turned left last year I’ll turn right this year. It may seem like a waste of time but it never is—even if I don’t produce any photos as a result—because I’ve encountered something new about a place that I thought I was familiar with, and the more intimate I become with a place the better I can represent it in a photograph.

moreConfusing the Subject for the Photograph

There is a phenomena I’ve noticed, especially online, regarding how people respond to photographs. In particular, what it is that will trigger someone to respond positively and regard a photograph as “good”. There are a number of things that a trained photographer, either formally or self-taught, will look for in a photograph during a critique. Technical aspects such as focus and effective use of depth-of-field, and artistic choices such as framing, spatial relationships between fore, middle and background, and choice of lighting. Elements of art such as line, shape, form, color, etc, and successfulness of expressing a concept, idea or emotion. But many times I have seen photos that are technically imperfect, devoid of artistic flavor and seem to say nothing. Yet they are highly complimented and rated. Why is that?

My answer is what I call “confusing the subject with the photograph”. Let me give you an example. A person shows a group of friends a photograph of their newborn baby. Everybody admires it and comments on what a great photo it is. But is it a great photo, or a great subject? For another example, let’s consider the deluge of selfies of scantily-dressed women that are posted to social media on any given day. There’s no shortage of men who will comment on how great the photos are, but considering that these images are generally made by a woman standing in her bathroom, lit by fluorescent lights and pointing a smartphone camera into a mirror, I don’t think I need to spend a lot of time arguing that the lighting and styling of the photograph aren’t exactly artistic or even ideal.

moreBreaking the Inertia

Last week I returned from a month-long road trip. I’ve been on the road a lot lately. In fact, I’ve put over 18,000 miles on my truck since July 1st of this year. I’ve been doing a lot of driving, a lot of hiking (well over 100 miles) and a lot of photography. What I haven’t been doing is a lot of writing. I carry my laptop with me, ostensibly to write blog posts in my spare time, but after a day of lugging all my camera gear through 14 miles of Utah canyons, when I get back to my truck I feel less like writing and more like passing out. String together days, then weeks, of that kind of activity and you end up with a lot of blank pages in your blog.

The situation lead me to think about the times I’ve felt the same way about taking the camera out to make some photographs. There have been days during my photography trips when it’s raining, or very windy, or snowing, or blazing hot or freezing cold. This past summer and fall I was caught in many hail storms in Colorado and South Dakota, and was temporarily trapped by a flash flood in a mountain basin in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado. There are many days when my muscles are sore and feet ripped up from the previous day’s marathon hike. Days when I’m tired because I’ve strung together several consecutive nights with four hours or less of sleep. Days when the light is too harsh or too bland for the photos I wanted to make. Days when I feel completely burned out or unenthused.

moreBe Fluid

One thing I have learned as a landscape photographer is the ability to adapt to rapidly changing situations. I can tell you from nearly 14 years of experience on the road that things rarely go according to plan. In the early days I would struggle against unforeseen circumstances and try to force my predetermined agenda to work in an environment it was no longer suited for. These days I try to roll with the changes, not only because I tend to get better results, but also because it’s the path of least resistance.

The plan is now just a guideline. It’s a framework but within that framework there should be a lot of room to maneuver. At the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, a tenor saxophonist named Paul Gonsalves was playing on stage with Duke Ellington’s orchestra. They were performing Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue when Ellington gave Gonzales a solo. Gonzales improvised for 27 choruses, bringing the audience to its feet. The written score was the plan, but it became a little more than a safety net. Like Gonzales, a good photographer should have an open and nimble mind, capable of seizing an opportunity and running with it.

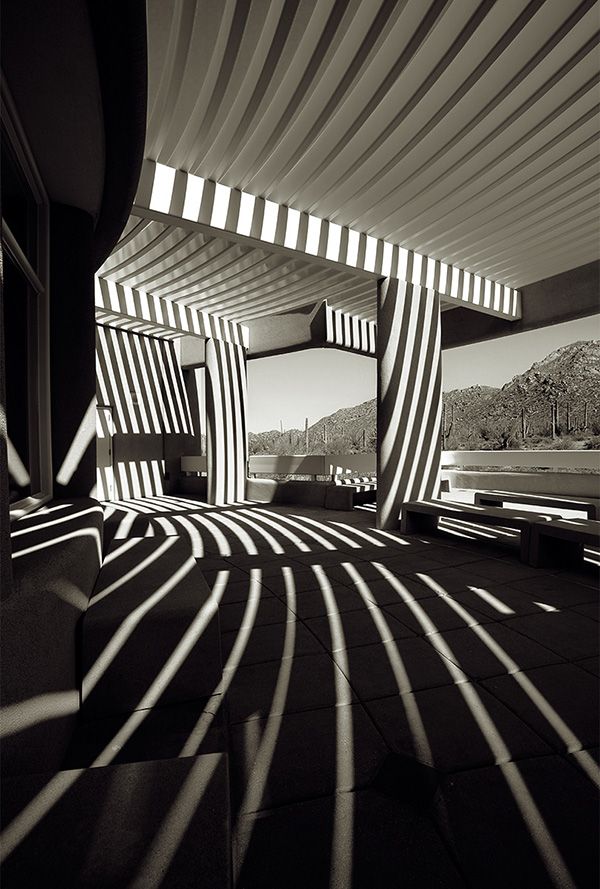

A common example from a typical road trip would be that I am hoping for a beautiful sunrise with dramatic clouds in the sky. The reality is that I rarely get them. So if the sky is clear does that mean it’s time to throw the gear back into the truck and call it a day? No, it’s just time to switch gears. Empty skies usually mean wide landscape shots are not optimal, but tighter, intimate landscape shots may work. Also, the contrasting light is favorable to black & white photographs. Maybe instead of documentary style photography, finding shapes, patterns and textures to create abstract designs would work.

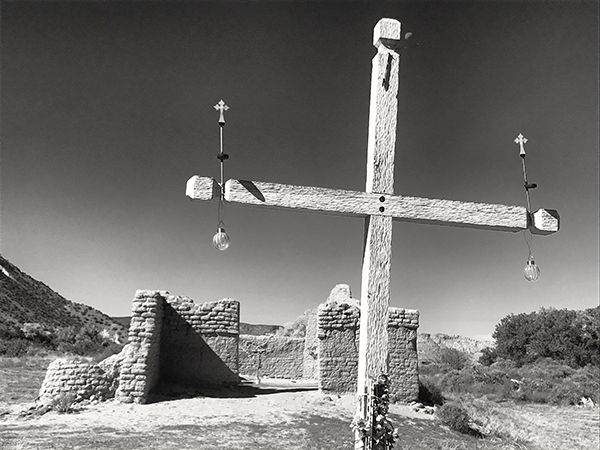

moreRiding the Rails in the San Juan Mountains

I have a deep-rooted interest in history, and it’s reflected in the subject matter that I enjoy photographing. Ghost towns, mining towns from the 1800’s, Native American ruins, Spanish Missions from the colonial days, Native American rock art and American Civil War reenactments are some of the things that attract me and capture my imagination. So it’s no surprise that when I had an opportunity to ride on an old-fashioned steam train over the Fourth of July holiday weekend, I jumped at the chance.

My wife and I met with other family members in Chama, New Mexico, home of the Cumbres & Toltec Narrow Gauge Railroad. The section of rail we would be traveling on was originally constructed in 1880 as part of the Rio Grande Railroad’s San Juan Extension, which was designed to serve the mining district of the San Juan Mountains in southwestern Colorado. Rather than boarding the train in Chama and riding to it’s terminus in Antonito, Colorado, we took a bus to Antonito and rode the train back into New Mexico. It had been suggested to us that that north to south was the best direction to travel since Antonito is in a desert environment, and it can be a bit anticlimactic after traveling through the mountains and forests nearer to Chama.

more