A few years ago I was photographing at the south rim of the Grand Canyon at sunrise. A German tourist approached me and started a conversation, and after a while as the sun climbed higher in the sky, I stopped shooting. Noticing this, he asked why I stopped and I told him the light had become too harsh for the type of images I was trying to make. He said, “Ah, so the light has become evil then?” The comment made me laugh, but it also made me stop and think about how photographers view light.

You won’t have to look very hard to find books, magazine or online articles with titles like, Shooting in Crappy Light, Taming the Mid-Day Sun and How to Make Great Photographs In Bad Light. But what is “bad” light, and does such a thing even exist?

In my commercial work of environmental portraiture, it’s common to have the client want to be photographed outside in front of a corporate building or on an industrial campus. It’s also sadly common that the only available time they have in their schedule to shoot is 11:30am or 1pm, or some other time of day where the sun is directly overhead and creating harsh lighting. If I place my subject under that light the results aren’t going to be pretty. My inclination in that type of situation is to look for open shade of any kind; a place that offers even lighting that I can control relatively easily. If I can’t find any open shade or the client has a specific location they want to use that doesn’t offer any, then I have to build scrims, use reflectors or introduce flash into the equation. This is the hassle and heartbreak that created the myth of “bad” light; situations where photographers have to struggle and wrestle with the light in an attempt to conquer it rather than having the flexibility to work with it. To take advantage of the available conditions, I like to use the sun as a rim light or accent light, saving me the trouble of setting up another flash and also giving me a sense of having turned the light to my advantage.

For my personal work and even commercial landscape and architecture projects, I can be a little more fluid and adaptive with what nature is giving me on any particular day. I’ve written in previous posts about the value of being able to roll with the changes on set or on location. For landscape work I prefer low, angular side lighting or sometimes backlighting. But if nature isn’t cooperating there’s no point in banging my head against the wall and trying to force something that isn’t there. It’s time to reevaluate the light and decide what it’s suited for. Great light can overcome weak composition, but great composition cannot save an image made in inappropriate lighting, so I like to allow the light to suggest how the shot is going to play out.

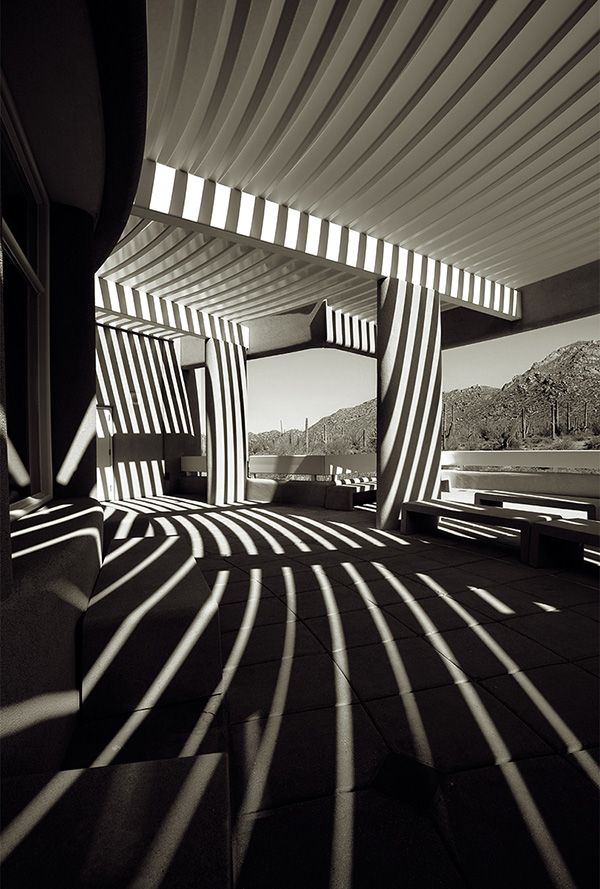

The example image I’ve included in this post is a result of being flexible and sensitive to what the light was offering. I was photographing landscapes on that day and due to the cloudless sky, the window of light that had favorable qualities for my landscape work was very small. Instead of packing up my gear after that window closed, I began looking for subjects that the light was ideal for. High-contrast light and strong shadows are well suited for black and white photography, and architectural work in particular. Shooting in light that was unsuited for the type of landscape work I do, this architectural shot takes on a strong graphic quality that feels powerful and iconic. It actually benefits from what many photographers would deem as “bad” light.

Light is neither good nor bed; it just is what it is. The same light that may be great for one subject may be inappropriate for another. Instead of trying to force a square peg into a round hole, look for the opportunities offered by the light you’re presented with. It may lead to a stronger image than the one you had originally envisioned.